Welcome to Hurlothrumbo.com History Lesson

Joshua Norton arrived in San Francisco Bay as master of

the steam yacht Hurlothrumbo on November 23, 1849. He got rich

trading commodities but lost it all by 1853 when he tried to corner the rice

market. Norton is best known for declaring himself "Emperor of the United

States and Protector of Mexico". While Norton never regained his fortune, he

lived out his days royally in San Francisco by issuing "Bonds of the Empire"

and accepting free meals from willing restaurateurs. When he died in 1880

more than 10,000 people attended his funeral.

Joshua Norton arrived in San Francisco Bay as master of

the steam yacht Hurlothrumbo on November 23, 1849. He got rich

trading commodities but lost it all by 1853 when he tried to corner the rice

market. Norton is best known for declaring himself "Emperor of the United

States and Protector of Mexico". While Norton never regained his fortune, he

lived out his days royally in San Francisco by issuing "Bonds of the Empire"

and accepting free meals from willing restaurateurs. When he died in 1880

more than 10,000 people attended his funeral.

The life of Emperor Norton was well documented in the San Francisco newspapers while he lived, and there are many web sites retelling the story, but the story of his steamship Hurlothrumbo is poorly documented. The authors of this web site believe the story of the Hurlothrumbo deserves attention.

The steamship, Hurlothrumbo, was built in 1841 at Laird's Shipyard in Glasgow, Scotland. Her predecessor on the ways was another little-known, but historically significant vessel, the steamship Nemesis. The Nemesis was significant in being the first iron-hulled steamship. Both ships pre-dated Isambard Kingdom Brunel's masterpiece, the magnificent Great Western, launched in 1844, by several years. The Nemesis was bought by the British East India Company and sent, by way of the Cape of Good Hope, to the Far East. The vessel was outfitted with two 24-pound cannon in Calcutta and sent to Canton as a part of the expeditionary force to punish the Chinese for destroying the cargoes of opium during the First Opium War. UCLA Special Collections has a copy of the fascinating volume, Voyage of the Steamship Nemesis, published in 1842.

|

|

I.K. Brunel |

The Nemesis and the Hurlothrumbo were nearly identical or as identical as was possible with the technology of the day. Both ships carried sails on two masts, and each had bunkerage for 300 tons of coal, giving a steaming radius of almost 800 miles. Sail was the principal propulsion, with steam used during windless periods and in harbor.

The vessels' power plants were single-cylinder, 28" bore, 84" stroke, low-pressure engines operating at 24 RPM. The boilers were inefficient tank-type, utilizing seawater, and operating at 6-10 psi above atmospheric. Skeptics have questioned this fact; the reality is that, with a boiling point of water at about 106 degrees C, there was little chance for fouling to occur. The contents were dumped periodically and replaced with fresh seawater. The engines were coupled to 24-blade side paddlewheels, operating in sheet-iron paddleboxes. From the notes of the day, the vessels were painted black, with red and gold trim.

There were separate "donkey" engines, single-cylinder units amidships, and used to hoist sails, weigh the anchor and to power small cargo cranes. The Hurlothrumbo first operated as a coastal freighter, traveling between London and St. Malo, France, in the then lucrative wine trade. The vessel ran aground, twice, on the Brittany Coast, but the durable iron hull remained sound. Her sister ship, returning from Asia after the victory in the Opium War, had her engines removed and spent the rest of her days as a sailing vessel, lasting until 1877, when she was broken up for scrap. The hull, of Swedish wrought iron, was still strong.

While the story of the Nemesis is fairly well documented, since it was so connected with the history of expansion of the British Empire, facts on the Hurlothrumbo have been harder to come by. Fortunately, there is sufficient primary source information at the Bancroft and Huntington Libraries to put together a good bit of the story.

We know the ship was delivered to Norton in Brazil via Cuba where a cargo of rum and cigars were taken on. The ship is described in Norton's diaries as his "yacht", but it was clearly a commercial ship even if the "captain's quarters" were fit for an emperor. Norton had extensive modifications made to the ship in Brazil where he expanded the master cabin and added a smoking room and bar. This displaced the officers who were forced to sleep below decks with the crew, but Norton's charm, generous table and liberal rum allowance won back their loyalty. While Norton called himself Captain, it was in title only. Captain Fitzgerald remained in charge of the sailors, and technical operation of the ship was left to the chief engineer Joseph S Potter.

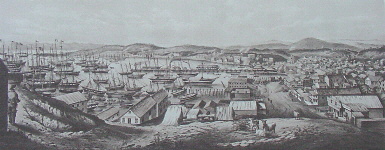

When Norton arrived in San Francisco Bay in 1849, it was already crowded with abandoned ships. Below is a picture of San Francisco Bay at that time. Click on it to see a larger view.

Ships arriving in San Francisco at that time were abandoned by their crews who headed for the gold fields. Norton's crew was no exception, but this was of little consequence to Norton as his cargo of rum and cigars which had cost him $5000 in Cuba could be worth a million if sold to gold miners. Captain Fitzgerald led the crew in abandoning the ship, but negotiated two barrels of rum as back pay. He opened a saloon on Polk Street and years later became one of "Emperor" Norton's most loyal supporters.

Norton had hoped to use the ship as a coastal freighter, but lack of coal on the West Coast meant the boilers must be fired by wood. As the engine was not (by modern standards) very efficient, this required huge amounts of wood. The Hurlothrumbo made several trips to the Farrallon Islands to harvest cormorant eggs from the nesting areas. These were preserved in sodium silicate (Water Glass) and taken to the Diggins and sold for up to $1.00 each. The successful 49'er who sat down to a plate of Hangtown Fry was probably eating Delta Oysters, soda crackers and cormorant eggs. The fishy taste was probably masked by the rancid salt pork used in place of bacon.

Eventually Joseph Potter reluctantly came to the conclusion that the Hurlothrumbo would be more valuable to her master if she were scrapped. In England Potter had been apprenticed to Boulton & Watt the famous steam engine designers. He is credited with the installation of a number of pumping engines in Welsh coal mines, including the famous "Puffing Billy", at the Llanfairgough Mine, kept in continuous operation until 1946. Potter believed that the equipment on the Hurlothrumbo could be put to profitable use in California's gold mines.

With Norton's blessing, Potter commenced dismantling the Hurlothrumbo. The hardwood fixtures in the "captain's cabin" were carefully dismantled along with the smoking room, bar and elaborate brass fixtures. The sails were sold to a tent maker, and planking, masts and interior woodwork were sold as building materiel.

Engineer Potter salvaged the donkey engine and boiler from the Hurlothrumbo's hull. The forgings of the main engine would have weighed some 40 tons, and there was no shipyard in San Francisco capable of rigging the larger components from the engine room. As for the hull, while most of the wooden-hulled derelicts were scrapped or burned, there is no evidence that the hull was broken up. There is one very interesting reference to the finding of a wrought-iron hull in 1903 near Fort Barry, on the Marin side of the Bay. Fort Barry, one of the Endicott-Period coastal defense forts built to guard the Bay and its valuable anchorage, was one of the control stations for a stationary minefield. During a practice laying, the mineplanting vessel, San Jacinto, fouled her sea anchor. Unable to dislodge it, the Army hired the Taliaferro Brothers Salvage Company to send a diver down. The hard-hat diver descended to 100 feet, and found the anchor "fouled on an iron-hulled scow, bearing unusual rivet patterns and the remains of paddleboxes." The anchor was finally retrieved, and the incident forgotten. Was this the hull of the Hurlothrumbo? We probably will never find out.

While Potter was disappointed to be taking apart the Hurlothrumbo, he felt he could make his fortune by constructing steam powered mining equipment using the Hurlothrumbo's engine and boiler if only he could get the equipment to the diggins. By the time Potter got to Old Dry Diggins (later known as Hangtown and today known as Placerville), he learned his fortune was not to be made in mining engineering, but in cigars. He found a ready market for cigars at $10 each or a half ounce of gold for a cigar. In today's dollars that is about $160 for a cigar, but the miners were willing to pay the price.

Potter did get to do some engineering. With a Chinese partner he set up a laundry and bath house using the Hurlothrumbo's steam engine, pumps and boiler. Potter may have invented the first clothes washing machine, but no details of his design have survived. We do know he offered a "free clean shirt and bath" to anyone who bought one of his cigars, and he had no shortage of customers.

Potter sold the rum and oak paneling to Edward Dibble who opened a saloon in what is now Placerville.

Within a month Potter returned to Norton in San Francisco with $20,000 in gold. Norton had been making money trading in commodities. He had purchased a ship load of coffee at a low price from a Brazilian captain as nobody in the customs office could speak Portuguese. He made money buying oranges in Tahiti and selling them as a scurvy cure to miners who had been subsisting on bacon and beans for months. But nothing was as profitable as the cigars, and they were running out. Norton was smoking 20 cigars a day and spending money faster than he could make it.

In April of 1851 Edward Dibble announced himself at Norton's hotel as "Edward Dibble Noble Grand Humbug of the Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampis Vitus". Norton's diary describes Dibble as dressed in a formal beaver hat (somewhat worse for wear), a leather vest with many ribbons and badges of "cryptic insignia", a red union suit, suspenders and canvas broadfalls "several sizes too large." (I am preserving Dibble's spelling Clampis rather than the more common Clampus.)

Dibble announced to Norton that he had come to San Francisco to purchase one of "them thar hurlothrumbo machines", and that he had told the Noble Grand Gold Dust Receiver to "send out a call for gold dust amongst the brethren" and "that call had been deemed satisfactory and so recorded." After a fair amount of whiskey, some whisky and no small number of cigars Norton, Potter and Dibble came to a mutual understanding as to what "one of them thar hurlothrumbo machines" was.

Potter's arrival in Old Dry Diggins on his wagons loaded with the steam engine, brassworks, cigar humidor, and barrels of rum had made a great impression on Edward Dibble. He declared "It was more exciting than a circus parade."

Old Dry Diggins was soon to be the terminus of a railroad to Sacramento, and the town was growing up. Dibble pointed out there were many places where miners were still living in tents without hot food, baths and more importantly a bar and cigars. The rum barrels stenciled with "HURLOTHRUMBO" had reminded everyone of the day Potter had come to town with his cargo of hot baths, good rum and great cigars.

Dibble wanted Potter to build him a wagon that would carry a steam engine, bar, humidor, kitchen and baths. It would be hauled by mules, and could pump water from a stream and set up business wherever there was water and wood for fuel. Dibble called this thing a hurlothrumbo, and the brethren had ruled it "satisfactory and so recorded".

When Dibble presented a sack with $10,000 in gold dust with a promise of $10,000 more on delivery, the Norton Hurlothrumbo works was born. Norton demanded the sole right to sell cigars through the Hurlothrumbo, but this never proved lucrative as the price of cigars fell once the shortage was relieved in the summer of 1852 by regular shipments from Panama.

One historian has suggested that the need for hot baths in the diggins was demanded by certain female "camp followers". Norton's diary includes Dibble's calling card which indicated he was "dedicated to the care of widders and orphans, but primarily widders." (In Latin no less!) Norton noted in his diary "I don't believe him, but the gold is real."

Potter set to work salvaging engines, pumps and mechanical works from the Hurlothrumbo and other ships in the bay. There was plenty of hardwood to build the bar and humidors. The wagon was built from virgin redwood with lots of brass fittings and great leaf springs. It took fourteen mules to haul it, and it was delivered to a Clamper "doins" at Angels Camp on October 31, 1851. It was a great success with the brethren. Dibble announced "E Clampis Vitus is spreading through the diggins like wildfire". Every Clamper who saw the hurlothrumbo wanted one for their camp.

At the dedication of the first hurlothrumbo, Potter promised the crowd that the next hurlothrumbo he built would "make ice in the summertime". He was greeted by jeers from the crowd and promised "Ice or the next one is free." Dibble addressed the group and called for donations. Within a few minutes 1000 ounces of gold or $20,000 was collected by the brethren and presented to Norton as a $20,000 deposit for a second and grander hurlothrumbo to be delivered in August 1852.

Almost a decade later Mark Twain wrote about the arrival of the hurlothrumbo in Angels camp in an unpublished manuscript he submitted to New York Saturday Press. The article was rejected as "too fantastic", and he submitted "The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" in its place. The original manuscript is in the hands of the Sorocco family, long time residents of Placerville and active in the restoration of E Clampus Vitus in the 1940s.

The "second and grander" hurlothrumbo never was built. Tragically Potter was killed, and the Norton Hurlothrumbo Works was destroyed by an ether explosion in June 1852. Potter had demonstrated that he could generate "ice from steam", but the ether vapor used in his refrigeration process was highly flammable, and refrigeration did not become practical for another 40 years.

John M Studebaker must have seen and been influenced by Potter and his hurlothrumbo. At this time he was manufacturing wheelbarrows for miners and was a member of E Clampus Vitus. In 1858 he returned to Indiana to make wagons and later automobiles. It would be historically significant if we could prove a link between the wreckage of the hurlothrumbo today near Murpheys California and Studebaker, but the evidence just isn't there.

There is another interesting connection for Joseph Potter. We know that he made at least one trip to the United States in 1846. He was laid up with malaria on a trip along the Gulf Coast to New Orleans. He was put ashore in Apalachicola, Florida, and given over to the care of Dr. John Gorrie, a physician who operated a clinic to treat U.S. Navy sailors from the anchorage at nearby Pensacola. Gorrie had pioneered designs for steam-powered cooling and refrigeration equipment. His goal was to cool his wards when the malaria victims went into the acute stage and ran high fevers, and when ice was only available at over $1.00 a pound. He was also able to provide ice to chill the champagne during the July 4th celebration in 1847, attended by the French Consul from New Orleans.

Gorrie's story is detailed in the July, 2002 Smithsonian Magazine. We know that Potter was a patient of Gorrie's, since his name appears in a ledger kept in the Gorrie Museum. Gorrie, by the way, is honored by his statue in the U.S. Capitol Statuary Hall, in commemoration of his great invention. Potter may have seen the apparatus, and may well have attempted to duplicate it.

By 1853 Norton had lost all his money, and shortly thereafter he declared himself "Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico". Dibble and the Clampers never held Norton accountable for the money they lost. They treated Norton with great respect referring to him as "El Sublimo". Today all members of E Clampus Vitus honor the memory of Norton, but Potter and the hurlothrumbo are only known to a select few that still "raise a toast to the hurlothrumbo".